By ICG member Kevin McLean, Wardle McLean

Pic: Goofy in Disney animation, Motor Mania

I’ve been researching motor insurance. Before you glaze over, it has revealed both a Fundamental Truth about human nature and a persistent marketing ‘blind spot’.

The FT is the (in)famous ‘say-do gap’. People don’t do what they say, or say what they do, especially in a research context. Specifically, what people say (testimony, attitudes) is a very poor predictor of what they then do (behaviour).

In our study, 86% of our sample said that they believed they were good drivers. This is backed up in other studies.

How to deal with the say-do gap in research, given that we cannot change human nature? In his excellent recent article, The Say-Do Gap in Driving Behaviour, Simon Shaw of Trinity McQueen outlines three key steps:

- use multiple sources/methods

- get real ie study actual behaviour (as well as reported behaviour)

- do this over time, rather than as a one-off snapshot

But it goes even further: the say-do gap is a perennial marketing issue due to a confusion between two communication modes. Organisations often use the rules of the first mode to judge speech in the second mode.

In ‘contract mode’, statement and behaviour are directly and explicitly connected. The ‘keep off the grass’ sign on the lawn, marriage vows or sworn legal testimony, are examples of contractual speaking, tied to behaviour, occurring within an agreed frame of reference.

But most interactions are in ‘conditional mode’, where speech is conditioned by a host of factors, such as context, what’s at stake, who is speaking and why, the emotions at play. ‘I’ll go the gym 3 times per week’, ’14 units of alcohol per week’, ‘Let’s have a coffee some time’, are all be examples of this mode.

Qualitative research tries to recognise and mediate between these different modes. Client organisations (in contractual mode) may want the public to do X, for Y reasons; the public may or may not want to do this, it all depends, but will nod and smile in either case.

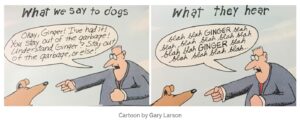

Driving is a great example of ‘mode confusion’. The question ‘have you broken the speed limit’ is asked in contract mode, directly about a specific behaviour, but is received conditionally, ie the framing changes, leading to a communication mismatch, similar to the famous Larson cartoon:

Breaking the speed limit is illegal and potentially dangerous; the question carries social and psychological ‘baggage’ and brings a host of other questions eg what is at stake, what should I say, have I gone too fast by mistake etc? How people answer a question, in research and in life generally, reveals how they position themselves, not what they do.

One final point, let’s call it the ‘say-do switcheroo’: rather than studying how attitudes (testimony) predict behaviour (spoiler alert, they don’t), why not look at how behaviour affects attitudes?

In our study on driving behaviour, we looked at how feedback loops inform drivers. This is increasingly common with newer cars, which nudge us with various beeps and dashboard signs (car ahead is moving off, lane assist, parking sensors etc).

With telematics feedback, drivers see for themselves whether and how often they have strayed over the speed limit, braked or accelerated harder than normal, etc. Reflecting on this behavioural information seemed to affect how people then spoke about their driving.

With the right design and with enough time, research can learn about behaviour and use behavioural input deliberatively to close (and reverse) the say-do gap and thus suggest ways of changing behaviour.

Summary:

- the say-do gap is a people thing, not just a research thing

- knowing it is there and how it operates (cf communication modes) is the first step

- using multiple research inputs, including actual behaviour and feeding this back

- over time allows for behaviour to inform testimony, for more accurate insight.

http://www.wardlemclean.co.uk/