ICG member Iona Carter examines how people shop and what retailers can do to influence them.

The Nobel Laureate psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, famously said that “thinking is to humans like swimming is to cats… they can do it, but they’d prefer not to”. And this is as true for humans as shoppers as it is for any other identity we take on in our daily lives.

So, why does much of what we see in our retail environments appear to assume otherwise? Why, for example, do we expect shoppers to read the equivalent of War and Peace on our POS, when they’d really rather not… or more to the point, when they simply don’t? Why do we so often see brand-centric, feature-led communications when all shoppers want is to recognize, with ease, that products will deliver against their goals, or their jobs to be done? Why are product displays sometimes so fragmented that it’s almost impossible for shoppers to easily find a good starting point from which to browse and engage with the offer?

The answer is that brand and retail marketing and design all too often falls foul of the tendency to believe that shoppers are prepared to put in the effort, that they are always ‘on’ and will therefore be bound to see, engage with and consider whatever is put before them.

But, they’re not… and they won’t, by default… because oftentimes, they simply can’t.

Returning to Kahneman for a second, possibly his most impactful and well-known contribution to our understanding, and, consequently, how we should adapt our Marketing is how he conceptualized the way we operate mentally and make decisions. “System 1 / System 2 thinking” has become a familiar concept for most, the former acting as our ‘always on’ autopilot and the latter acting as our ‘sometimes on’ pilot. System 1 is reflexive, fast, automatic, intuitive, virtually limitless in its capacity and largely subconscious; it helps us navigate our lives with minimal effort, making decisions on what we attend to and how we respond based on learnt, associative memory networks and millennia of evolutionary adaptation. System 2 represents our reflective thinking state, it kicks in to help us deal with unfamiliar situations, with more complex, involved problems, and occasionally to over-ride System 1. System 2 thinking is effortful and deliberative… and often what’s required to make sense of complex retail spaces and communication – yet it is, as Kahneman said, the swimming of the feline world, and we prefer to engage with it sparingly.

Paradoxically, though often required to decode complexity – System 2 can be “switched off” by the same in retail environments. Too much choice, incoherent displays, or complex messages are often too much for shoppers to willingly deal with, resulting in a tendency to revert to System 1 modality. Other factors can also turn the lights out for System 2: low involvement with the category, information overload and time pressure can all mean that shoppers naturally, and without thinking resort to autopilot behaviours as it’s easier and quicker to get the job done this way.

So, no wonder much of what is done on the shop floor (or, indeed, on the website) fails to achieve its objective: it’s talking to the wrong ‘system’! In order to talk to and influence shoppers, we’ve always got to be prepared to talk to their autopilot, System 1, and this is where applying the principles and disciplines of behavioural science can be invaluable.

And let’s not get put off by the ‘science bit’… this stuff really isn’t scary! Small interventions and changes can make big differences:

We can improve noticeability of displays and communications for example, by applying the principles that dictate how we physiologically and mentally perceive the world around us. Since humans don’t see with 100% clarity beyond 2 degrees of where our eyes are focused at any one time, getting communications or products noticed requires that they must cut through the blur of peripheral vision. For example:

Use of colour and shape contrast in this display creates visual disruption that can cut through the blur.

Even the illusion of movement as seen here can attract attention… harking back to our Neanderthal ancestors’ very survival being dependent on their ability to detect movement in their surroundings.

Furthermore, our subconscious constantly scans the environment for signals that imply goal relevance, directing our attention towards things that can help us achieve our goals at the time. So, knowing your shoppers, their goals, motivations and expectations will help design environments, product ranges and interventions that will be more attractive to the autopilot shopper.

Behavioural science can also help guide how promotions and prices are communicated. For example, size congruency theory tells us that, contrary to typical practice these days, a promotional price should be displayed in smaller font than the original price. It makes the message easier to process… and fluency of processing translates into preference.

In this study, shoppers exposed to the price label on the right exhibited a 25% higher likelihood to purchase than those shown the label on the left. And yes, this effect has translated into the real world outside of the lab environment!

Source: Keith S.Coulter1Robin A.Coulter2

Size Does Matter: The Effects of Magnitude Representation Congruency on Price Perceptions and Purchase Likelihood

Journal of Consumer Psychology Volume 15, Issue 1, 2005, Pages 64-76

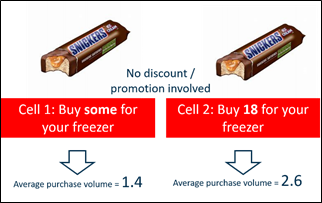

As a last example of how the principles of behavioural science can be leveraged to good effect, behavioural economics gives us the concept of nudges: small environmental interventions that change the decision interface in order to trigger the desired behaviour. They work on the principle that our behaviours and decisions are often influenced by subconscious mental short cuts (heuristics), and biases… System 1 again! The anchoring bias for example, works by introducing a number as a reference point which has an implicit impact on ensuing behaviours and decisions.

In this example, shoppers were presented with an invitation to purchase under two different controlled conditions. Those who had been primed with the number 18 subconsciously anchored on this number and went on to buy 85% more ice creams than those invited to simply buy ‘some’.

| Source: Brian Wansink, Robert J. Kent, Stephen J. Hoch: An anchoring and adjustment model of purchase quantity decisions |

To conclude, there is much to be gained by recognising four basic truths about shoppers:

- Just as cats don’t like to swim, they don’t like to think an awful lot: make it effortless

- They are conditioned by millennia of evolutionary adaptations to attend to certain types of stimulus: make it intuitive

- They don’t shop for the sake of it – there is always a goal to be met: make it relevant

- And finally, they are more likely to take action if given a little nudge: make it happen